Now Reading: “I never said surfing was fun”—a super frank conversation with Matt Warshaw, surfing’s ultimate custodian

-

01

“I never said surfing was fun”—a super frank conversation with Matt Warshaw, surfing’s ultimate custodian

“I never said surfing was fun”—a super frank conversation with Matt Warshaw, surfing’s ultimate custodian

You can listen to The Wipeout Weekly episode with Matt Warshaw, the author of Encyclopedia of Surfing and History of Surfing on your preferred pod platform or below.

Transcript follows: Zuz Wilson | Host, Matt Warshaw | Guest, Campbell Wilson | Fan

Matt: I never said surfing was fun. I think it’s, I think what surfing is, is absolutely addictive and compelling. And it was like a project.

It was like a project, or maybe even some kind of very difficult game where there’s level to level to level. It was never fun. And it was very, very rarely that I feel satisfied with it.

But if I did get to that place now and then, then that was the best I’ve ever felt in my life. So every now and then, if I was, and it usually didn’t happen until I was pretty close to exhaustion because I’d never surfed well until I was really tired.

Zuz: Welcome to the Wipeout Weekly, the daily podcast for beginners, wannabe surfers, and seasoned Wipeout enthusiasts.

No hype, no filler, just the highs, lows, and honest truth about learning to surf and finding your place in surf culture. I’m your host, Zuz Wilson. Let’s go out.

Matt: But I mean, you’re such a surf freak now.

Zuz: I am, I am. I love writing about it.

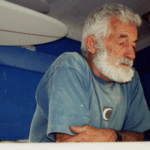

Matt: Are we rolling right now? Yeah, good, good. Because I just want to say, you got in touch with me and I look at this photos of you and I was reading your email to me and part of me was so jealous because you’re so enthusiastic and you have all this energy for this and every part of this seems interesting to you. And you know, I’m just at this, tending these last few embers of my love for surfing.

I really, I’m basically like, the whole thing with the work is sort of just, I’m just sort of scrapbooking and I’m putting back this stuff. I’m trying to organize it a little bit. But you, the way you get up, seem to get up every morning and it’s like surfing’s the thing that, what’s my, planning a day around, is the surf good or not good? If it’s not good, I can go to work.

If it’s gonna be good in the afternoon, I better get all this stuff done this morning so I can get out there and da-da-da. And I haven’t been that way for 15 years since my son was born. And I really, I don’t always miss it.

And I had so many decades where surfing was every day the thing that I thought of first. And I’ve just got on with things. I’m, you know, my life is just where it should be, but there are times now and then, and I felt it when I was, you know, reading, when you emailed me about how, you know, enthused you are, that I just go, oh my God, I really missed that.

Zuz: So I probably come across more enthused now than before because this is all I do. Like 14 hours a day. And I’ve been running this group of girls it’s called Girls Who Can’t Surf Good since 2017.

74,000 girls, like 33,000 of them active, which is amazing. It’s big, yeah. And it’s just, I guess it opened up surfing to me.

I always loved it. I loved history of surfing. The first time we saw “Riding Giants”, it was like, oh my God.

Campbell: And that was before we surfed. Yeah. It was a time out.

I don’t know if you’ve ever read Time Out Magazine.

Matt: Yeah, yeah. I used to read it all the time.

Campbell: It used to be brilliant. And then they were talking about “Riding Giants”, saying this movie is amazing.

Matt: So the guy who made that, Stacy Peralta, he and I were on the Zephyr team together.

So I knew Stacy, we were surfers. My whole thing with Zephyr was before the skate part of it. So I didn’t know this until a few years ago, but Zephyr came out of Jeff Ho’s surfboards.

Jeff Ho was first. And Jeff Ho was kind of new on the scene in 71 or two. And what I remember those boards for was that they had a guy named Craig Stasek who was doing these air brushes on them.

And so in 71 or two in California, the surf scene had gone really kind of underground and colors were out and everything was serious and humor was sort of out and the wetsuits were black and boards were white. I didn’t care that much. I was 11.

I was just so stoked to be in the water and stuff, but it was kind of a grim, sort of this grim period, not very colorful. And then these Jeff Ho boards came out. The boards themselves were kind of pointy in a way that when you look back on it now and think back, what were we thinking? You don’t actually need pointy surfboards to ride Santa Monica and Venice, but a pointy board really looks cooler than a stubby board.

So these beautiful pointy boards that Jeff Ho was making that were airbrushed by Craig Stasek, who I think got his start doing cars, like doing hot rods. I’m not sure about that. But the airbrush, and he wasn’t doing airbrush like scenes, like desert scenes or goblins and wizards.

He would just do like a thing with purple to blue to green, like these fades and sort of a wishbone thing. And there might be a few little stars or something in them, but these boards look so good. They look so amazing.

And no one will know how good they look because if you see them now, everything’s faded. So the boards don’t keep, they don’t last very well. Everything gets sort of yellowed.

But when we were, at 71, looking at these boards that were coming out of this new shop, this looked like nothing we’d ever seen. They were so beautiful. They looked so much better than any other surfboard.

So I wanted a Jeff Ho board, like more than anything I’ve ever wanted. And I got one when I was, I think, 12. And about two months later, it got stolen.

Zuz: Oh, it’s like your bike, Campbell.

Matt: Oh, if you get a board stolen at that age, it was heartbreaking. And my parents didn’t say we’re gonna go buy you a new board, but they said, if you work really hard, we’ll match the money.

Whatever money you make, we’ll match it. So I went and I did chores and I worked and my uncle was making a boat and I helped him make his boat. And I got up however much money I think I needed to get, maybe 75 bucks or something.

And they matched it and I had just enough. And I went back to the Jeff Ho store and ordered my next board. And three weeks passed and I went to pick it up and it wasn’t a Jeff Ho.

Oh. And it had this squiggly thing on it, this squiggly like, it wasn’t even a label. It was a bit of airbrush.

And I was trying to read it and Jeff was there or Skipper Emblom was there and he said, it’s a Zephyr. And I said, oh, it’s a, you know, and I just looked at my dad and he looked at, and it came out, I don’t, you know, I don’t remember the conversation. It came out though that Zephyr was the new line and it was the discount line.

Zephyr Surfboards was the discount line of Jeff Ho Surfboards. So, you know, I was pretty bummed out. You know, I was just going, wow, I really thought I was getting a Jeff Ho and I got a Zephyr.

And at that point, it didn’t mean a thing. That was the first time they’d ever put Zephyr on anything. So I had the first ever Zephyr Surfboard.

And then, you know, after a few months or a year or two, Zephyr kind of became, Zephyr eventually kind of overcame or became bigger than Jeff Ho, the Zephyr team or the Jeff Ho Surf Team. The Surf Team was before the Skate Team. And then the Skate Team made everyone forget about the Surf Team because the Skate Team went, got so big and I wasn’t part of that at all.

But Stacy and I, Stacy Peralta and I, and a whole bunch of all these other guys that were on the, a lot of them were on the Zephyr Skate Team eventually, were all on the Zephyr Surf Team at first. And Stacey was the guy who I kind of identified most with. He was another like slightly, almost nerdy, like cool, like he had the same long hair I had, same skinny guy, we were both regular footers and neither one of us were crazy talented.

We were just, we just tried really hard. And I’ve liked Stacy a lot and we got along and he went on to fame and fortune with Powell Peralta and everything else he’s done. And I moved out of town and surfed and wrote books about surfing and stuff.

But he, I didn’t wanna do, I wasn’t riding giants, I didn’t wanna do that because I’ve got a lot of anxiety about sort of being on camera, being in public and Stacy called me up and just wore me down. And if I take enough Ativan and beta blockers, I can sort of get through those things. I used to have to do that for podcasts and I’ve gotten better at it.

So I can do this. Really? Yeah.

Zuz: Is that why you say that you hate podcasts?

Matt: I hate podcasts these days for a couple of reasons.

I don’t hate podcasts, I love podcasts. I hate doing them because I’ve done so many and I feel like I’m just repeating myself and I don’t wanna be the person that just goes on a podcast. But I also don’t like them because every day I walk around for, it’s gotta be two hours or something.

So I wanna get all my steps in. And I walk around listening to this podcast called “The Rest is Histor”y by these two British guys, British historians.

Zuz: This is the one that you recommended to me.

Yes. And I love it because it takes my mind away from everything. I’m not, it’s exactly what I want.

But some part of me in the back of my mind is just going, don’t ever do another podcast, Matt, because you’re never gonna be as good as these guys at what they do. They’re so funny, they’re so smart. And the fact that I know that I can never, I could never even touch the hem of what those guys do, being knowledgeable and conversant and funny makes me feel like, well, don’t do it then, you know? So I just, I don’t know.

Zuz: Let me put your mind at ease, it’s a different audience. It’s a different audience that’s gonna be listening to.

Matt: I totally know that. These guys and to the podcast that you’re going to do and they’re gonna enjoy it, definitely.

I know that. We’ll be fine, we’re good. I don’t hate doing podcasts.

I hate doing podcasts personally because I always feel like I just sound like an idiot because it’s so put on. It’s like, I’ve got my questions for you. I’m not gonna even look at them because this is pointless.

Whenever I look at prepared questions, it just doesn’t come out right and it’s not an interesting conversation. But the exercise is to prepare them. It’s true.

Once you’ve done that, then you don’t need to look at them. Yeah, if I didn’t do all this work, I wouldn’t know that you actually started surfing in a swimming pool. Yeah, my uncle Dan pushed me across.

He just died this year. Died a few months ago.

Zuz: Oh, I’m sorry.

Matt: No, no, no, he had Parkinson’s forever and he was not in good shape and it was okay. But he was a great, Uncle Dan, Uncle Dan, he was the happy accident for my mom’s parents. He came, gosh, he was 15 years younger than my mom and he was the golden child.

He was this beautiful blonde boy that my grandparents adored. They were always a little strict with my mom and her brother. So Uncle Dan came along just at the right time to sort of pick up on that sort of gidget phenomenon.

So he would have been in middle school probably when Gidget came out. And so when we were living in Tarzana, where I grew up, that’s my deep, dark secret. I’m a Valley kid.

I always say I’m from Venice, but no, I’m not really, I’m from Tarzana. We had a pool and I was five or six and Daniel, this is 1965, and Daniel came by with his big, I think a Hanson or something. And he would just put me on that board and push me across the pool.

My brother would bride on it too sometimes. And he would just say, okay, look, before it gets to the other side, I would stand on the board and take a surfing position, what I thought was. And he would push me and he’d say, okay, before it gets to the other side, you gotta get off and crawl to the front and stop it so it doesn’t bang the nose.

Because he didn’t want it to ding. Of course. And I was so lightweight that I could crawl to the front of the board and it wouldn’t go down, it wouldn’t pearl.

So I’d go down and I would stop and then he would turn the board around and push me again. So I was a surfer. We hadn’t even moved to the beach.

And then the funny thing was is my parents had no plans of moving to Tarzana at that point. And then two years later, very suddenly, it just happened, we ended up literally on the boardwalk, you know where the Venice jetty is?

Zuz: Yeah, of course.

Matt: We were the, if you stood at the jetty and turned around, the house is gone now, but we were the first house you’d see on the corner of, gosh, I think it was 21st and boardwalk, big, beautiful two-story house.

And I still remember the day we moved there when I was, I think, seven, in my room upstairs and the wind must’ve been howling and I could just hear this wind go whoo. And all it was, you know, outside was just, you know, beach and ocean. And I remember being kind of scared, you know, and my parents said, Ray, how are you gonna love it? And I did, you know, the minute, next, I don’t know, next day, but my brother and I took to the beach and met some friends and we were body surfing right away and spent a couple years doing that and then started surfing.

And, you know, I was only in Venice for seven years maybe, but it really formed, it was, you know, from age six to 12 and it really sort of formed a large part of who I ended up becoming.

Zuz: How often did you go out surfing? Well, I didn’t start surfing until I was nine, in the summer, so in the summer of 69. And Venice wasn’t a great place to learn.

I think it is now that, you know, I’ve walked that beach a few years ago and it’s really changed, the amount of sand out there has really changed since the 60s. And I think there are ways now where you can, places where you can sort of begin, but the first summer I surfed was, Jay Adams’ mom would drive Jay and I every morning, most every morning in summer to the north side of Santa Monica Pier, which, so we learned to surf on the north side of Santa Monica Pier.

Zuz: There’s no surf there.

Matt: I know, but I mean, there used to be, there used to be enough waves for us to ride waves, but we only did that for one summer and then we were down at where all the big kids hung out, which was at Pico or Bay Street. So, you know, you just go a few blocks up. So, but it used to be Pico and Bay Street, they would blackball it and all those big kids, middle school and high school kids would come to the north side of the pier where Jay and I were.

So in the mornings, we were just out there by ourselves and later on they’d come over and, you know, we would go hang out with those guys.

Campbell: Big fan of Jay Adams. What’s that? I’m a big fan of Jay Adams.

He was in that case. On my 40th birthday, because he was the one who said, I used that quote on Facebook, was it, you don’t get too old to skateboard. Oh, what’s the quote? I just forgot the quote.

You don’t stop skateboarding because you’re old. You get old because you stop skateboarding.

Matt: He was, as compelling a human being as I’ve ever come across, even when he was seven or eight, not compelling, what’s the word I want? Charismatic.

Like even as a little kid. He looks like, you guys don’t know this TV show because you didn’t grow up here, but it was a show called Dennis the Menace with this kid named Jay North, who was this little. I think we’ve seen photos, definitely.

Yeah, just little rascal of a blonde haired kid who was just always kind of a terror. And Jay was like that, except like scarier because Jay North and Dennis the Menace was always getting into kind of TV kind of trouble, you know, like, and Jay was always breaking shit and just causing us to, you know, we were always on the verge of something going really wrong. He was a fun guy to hang out with up until I, you know, he and I sort of split up.

We didn’t split up, we were good surfing friends until he moved to Santa Monica and I moved to Beverly Glen and we were still on the Zephyr team together. But we kind of came apart at a time when things started going a little sideways for him and didn’t go sideways for me. Not because we weren’t hanging out, just because I think he was sort of destined for that.

But he was even, you know, he was always the kid that you couldn’t keep your eyes off of.

Zuz: There’s an enormous picture of him in the toilet was the Venice Ale House.

Campbell: The Venice Ale House, yeah, I always take a selfie if I’m in there, it just covers one of the side walls.

It’s really cool. He’s on a skateboard. Yeah.

Matt: It’s funny, you know, he wasn’t the best skateboarder, but he was the one that looked the best on a skateboard. Like he just looked so good on it. But you know, Tony Alva and others of his crew were more talented, but Jay had the, Jay just somehow seemed to have the look and the attitude and he just seemed to encapsulate that whole thing better than anybody else.

He did. He was always a lot, he was much always a better surfer and skater than I was, which was I think in a way good for me because it taught me at a super early age that I was never gonna be the, you know, I was always gonna be, there’s always people that were gonna be sort of better at it than I was. But I even, I was the older kid, I was taller, he was cuter, everyone would sort of look at him and I was always in his shadow, you know.

But anyway, he and I connected not too long before he died, which was what I was grateful for. We didn’t talk for a long time, not for anything bad, we just went different ways.

Zuz: So when you moved, was it Beverly Glen? Did you still come to the beach and surfed?

Matt: I was in Beverly, my parents split up right before seventh grade and in seventh grade, my dad was living with somebody else and when they split up right before eighth grade, he and I went to Beverly Glen in this little tiny place.

And I was only there not even, just barely a year before I ended up moving to Manhattan Beach with my mom, back with my mom and brother. But in that year, that was a strange year because I was in eighth grade, I was new to the school. You know, seventh, eighth, ninth, I went to three different schools, which is kind of a lot.

But I was always, you know, again, I was a known like good surfer, which kind of gets you into the cool kids. So I didn’t, it wasn’t a huge trouble, but you know, not being next to the beach in the eighth grade was a bummer. And I did a lot of skateboarding and I had a few friends and I did get to the beach some.

My dad was good about driving me down and I had another friend who lived right across the street. So I kept my hand in for sure and, but I, in the summer before ninth grade, when I arrived in Manhattan Beach to live with my mom and to go to high school there, it was really nice being back at a place where I could just jump on my bike and cruise down and get in the water when I wanted to. What did you surf there? What board? What brand do you mean, or? Just size, was it a short board, long board? The board, it just, so I started surfing in 1969 and my first board, which was given to me by Uncle Daniel, who I was talking about, they used to do this thing in 68 and maybe into 69 as well, where there were so many old, all of a sudden passe long boards because the boards went short so fast and the older long boards, you almost couldn’t give them away and so if you had a secondhand long board, there was just, they were just pointless.

There’s nobody, I mean, people were literally just taking long boards to the dump, but if you were thrifty and if you were handy, you could strip the fiberglass off of a long board and then you’ve got a foam blank there that you could reshape. It was called like, you could reshape a board into a small board, sort of you could because if you think about it, have you ever seen like, have you ever seen a blank before it’s shaped? No, it’s got a lot of, it’s got a beautiful built-in curve to it. So if you’re taking a 10 foot long board, it doesn’t have much rocker, stripping it down and making a seven foot board out of it.

My first board, which is a seven four, was just really flat as a tabletop. It was just a, it was the color of that red rug right there and it was a pintail and it was just a really hard board to learn on. It was a seven four cut down.

It was called, they called them a cut down. And in 68 and 69, anything went. Like anybody had any crazy ass idea, you could just try it.

Like that was sort of the mood of the period. Like the mood of the time was, I’m gonna make a 21 inch wide board by, you know, five foot eight. I’m gonna make a seven foot four inch by 15 and everybody was just trying all this stuff.

So the kinds of boards that I had for those first few were just all over the place. My first board was a seven four by something. My next board was a four eight by 22.

I went from seven four to four eight. Well, I was tiny. I was tiny little guy.

And then my next board was a twin fin. Then my next board was a gun. Then my next, you know, it’s just all over the joint.

And by the time I got here, gosh, I was still riding a ridiculously long board. We all rode longer boards because we all thought we were surfing Sunset Beach and we weren’t. We were just surfing Bay Street or we were just surfing some dumb ass local beach break.

And like the boards didn’t sort of get sort of sensible for like what we were riding for me anyway and my friends until I was maybe 15. So, you know, I don’t really much remember what I was riding when I got here, but something would just catch your eye for reasons that probably had nothing to do with how I was gonna ride. If I had a cool color scheme or if it had the right label and you just go, oh man, I want that board.

It was, nothing about it felt very logical or scientific. You just, your board would catch your eye and your friend would be riding a board that was two and a half or two feet smaller than the one you rode and you’d trade boards and oh, this works way better. And then twin fins came in for a hot minute and then the twin fins went out.

And then two years later, twin fins came back in and it was just a big swirl for a while. And it was kind of fun, but if you go back and look at the movies from, surf movies from the first five or six years of when the boards went short, you really see people struggling against their own boards. And you also see some people who forever, whatever reason, often just by dumb luck, had the right board, were surfing so much better.

And a lot of it had to do with stuff that we weren’t paying as much attention to as we do now, which is just sort of not necessarily nose rocker, but just overall rocker nose to tail. That wasn’t something, how to keep that line, what is the optimal line for that whole thing from the nose all the way to the tail? Also optimal sort of thickness from tail, thicker and then thinner. These weren’t things that we were too concerned about.

People, for some reason, were really concerned about, do I have a swallow tail or do I have a round pin? The thing that actually makes sort of the least difference, but it looks like a tail fin or something. It looks like something that you’d wanna pay attention to. So we were not paying really attention to things that as much things that we should have that mattered.

For some reason, we were really concerned with how thick the fins were. And again, it makes a little bit of a difference, but in the grand scheme of things, not so much. So it was so hit or miss back then.

And again, it was kind of, and the other thing was is that all the boards then were made one at a time, hand shaped. So endless amount of times where I would have a board, not endless, frequently I’d have a board, it was my magic board. The magic board was getting old, it’s getting funky and I’ll bring it into my shaper and say, hey, Pat, can you dupe this board for me? Of course I can.

And he’d take it and he’d make a board that looked identical but they never ever worked identically. So that was, and people to this day sort of lament that we don’t have hand shaped boards, that the boards have now are mostly machine made. And I remember the minute those things came in, the machines going, this is it, finally.

Finally, these boards are gonna be, we’re gonna be able to make boards to, if you have a great board, that’ll be identical to that board. I was so stoked when the computers came in and when, I have all these great stories about all the guru shapers that I had to sort of went in with my, would you shape me a board? And got to watch and I love all the stories about all those, the shaper used to be such a, literally just like a bearded person on a mountain that you had to go to and hope that he would, that stuff was really fun. I liked the personality of that, but when it came down to just getting dependably good surfboards, they could make a good board but they could also make you a lot of bad boards.

Not any old.

Zuz: Campbell got his first board from Mollusk in San Francisco and it was a Fineline board by Brian Hilbers. And it was, we still have it.

Campbell: It’s an amazing board, so. Someone cycled over it, there’s a.

Matt: Oh no.

Campbell: I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the guy in Venice Beach, he rides a bike with American flags on it and he always goes champion and you’ve got to say it back to him.

It’s not a political thing, it’s just spreading joy. He ran over my board. Well, if he did it, you can’t really let it go, yeah.

Zuz: To be completely honest, you left it in a stupid place. I think it’s fixable. It’s fixable.

But I loved Campbell’s board so much that I thought, oh, I want one like that, but I want this to be shaped to my spec. So I found Brian from Fineline. He’s just this, it was just one guy.

Was it Thousand Oaks where he lived? It was kind of on the mountain. And yeah, and I worked with him and he shaped me this beautiful nine six that I have and I love it and it’s in my favorite colors. So it’s like in magenta and mint.

It worked the way you wanted it to. Oh God, yeah.

Campbell: I mean, it’s not- I think it’s nicer than my one.

Zuz: Of course it is nicer. It’s not ideal obviously for Venice, but it was not made for Venice. It was made for Bolinas in San Francisco, but I love that board.

And he doesn’t make boards anymore. So I cannot even go back and say, oh, can you just make me another one of these?

Matt: I mean, somebody could probably at this point computer image it for you and do something like that. I don’t know.

I was thrilled when all that stuff sort of happened. I missed, I mean, it was more fun. It was just sort of holding your breath and seeing how the board came out as opposed to just like every board being good was kind of more fun, I guess, but not really.

It was a bummer getting, it was a bummer getting a dud board. A bummer getting- And it still happens. Absolutely, yeah.

Zuz: I was just talking to a girl from my group and she said whenever she, when she started surfing, she went to a shaper and he made her something that he thought it was good for her, but it just totally, totally didn’t work. Right.

Matt: Well, in the case when that happens, you have to be good about taking it, just not, you just don’t want to hold onto those boards.

I remember getting bad boards and going, well, if I just keep riding it, I’ll figure it out. And it usually doesn’t work that way. If it doesn’t work good the first couple of waves, you can usually tell.

Oh, I could, you guys don’t sell much stuff, I can see.

Zuz: No, we don’t, no, we just keep on to everything.

Campbell: I try to, you’re more of a hoarder than me.

Zuz: I am definitely a hoarder.

Matt: What do, is we, you guys, is Venice Breakwater still a spot? Y

Zuz: Yeah. Yeah, that’s where we go out.

Campbell: Where, when you say the jetty, what, do you mean the pier or the rocky bit?

Matt: So the pier, the pier when I was here from 66 to 72, the pier wasn’t a surf break. Like the sand was really steep for, and I’m sure it was before, but the pier was always just a really close to the beach shore break. And I, now I know it’s actually become a surf break.

So I don’t know how that, or how or when that happened. The jetty, the little, the little perpendicular one was a pretty good winter break. And then the rest of the year was no good.

And the breakwater, we surfed, I guess, year round, but not a great surf break. And then it was really big. It would, there would be waves coming off the edges of the breakwater.

But the breakwater was like kind of the hangout spot. There used to be, I don’t know if there’s like a pavilion down there, like a center, like the break. So that’s kind of near where the skate park is now, right? Yeah.

Yeah. So the skate park wasn’t there, but there used to be a giant oil derrick right there. I don’t know if that wall is still next to the, where the breakwater is.

There was like a public, sort of a pavilion sort of thing where bands would play. And the basketball courts were over here and all that stuff. That’s where we used to go after seventh grade to sort of hang out and surf.

And I remember this one, there were so few girls that hung out with us. Girls didn’t surf, you know? And this one girl that did hang out with us named Jackie, I was in seventh grade and she was in eighth grade. And she was really, she was a nice, really nice person.

Eighth grade girls didn’t usually talk to seventh grade boys and she did, she was cool, you know, she was cool. And she was down there hanging out and she surfed a little bit, she didn’t surf too much. And the next thing I heard about Jackie Fuchs, F-U-C-H-S, was that she was Jackie Fox of the Runaways.

So my old friend Jackie became the first bassist of the Runaways. And that’s how I ended up, I didn’t reconnect with her, but she was this nice, you know, this nice surfer girl that ended up becoming a rock and roller. And I don’t know if you guys know the whole story of the Runaways.

There was a good movie about it. A great documentary about them. And she was the one that was probably sort of was abused in the whole thing and sort of turned out, kicked out of the band or left the band or something.

And it was all sort of a sad thing. But, you know, the first couple of years of the Runaways, it was a big deal. And, you know, this local girl was part of it and we were all pretty happy about that.

So that was my other, that was my other touch, brush with fame was being friends with Jackie. Her nickname actually before she was Jackie Fox was she was Malibu Barbie.

Zuz: Did she look like Malibu Barbie?

Matt: No, she had brown hair and lots of freckles.

Yeah.

Zuz: So no girls in the lineup when you were growing up?

Matt: None.

Zuz: Wow.

Matt: I mean, but remember, my sample size is pretty small. Yeah.

But, you know, when I was, again, if I, when I was surfing at Pico, when I was surfing at Santa Monica Pier in Venice, no women that I remember. And then also when I went up the coast of Malibu, you know, nobody that I, I mean, I feel like I would have stood out. So, you know, you know, you would have, you would have looked at all that.

I mean, you can tell that just by looking at the surf magazines from that period. There was no encouragement certainly to, to surf. So it was pretty, it was, you know, and it was a boy’s club and it was, it was funny in that way that it was just dudes being dudes.

It was also just a bit much. It was, it was relentless, you know, and it’s a nice, it’s a, the surfing world is a much, much nicer place for there being women in the water. The last time I surfed, last time I surfed for a few days in a row anyway, was I went in the Southern end of Costa Rica last year.

And the lineup at this break we were at down kind of near Pavones was probably half female. And it’s just a, it’s just a, you know, it’s just a better, everyone behaves better. Everyone’s nicer.

It’s still, it’s, you know, it’s not not, it still can be cutthroat. You know, there’s still people doing things, but it’s just wasn’t as much, didn’t feel as tense. It didn’t feel as if something was gonna happen or break out.

It was, it wasn’t gonna happen that way, you know?

Zuz: Yeah, we’re trying to normalize smiling in the lineup now. This is, this is our, this is our mission. I was just talking to Kyla Peterson.

She runs Surfin Fire Oceanside surf school with her dad. And she was just talking about how her mission is to like instill more confidence in women who want to become surfers. But she just wants to get more girls into the lineup because it changes that energy.

And I am all for it.

Matt: The trouble is male, female, whoever, is that it’s always the trouble is that there’s not enough waves to go around. There’s just not.

And you can be as smiley and as friendly as you want, but at some point, everybody feels like they’re getting less waves than they should be getting. And then it just gets, and it’s difficult.

Zuz: Well, we were talking about it as well.

I asked her, do you think at some point, there’s just gonna be too many people in the water? And her opinion was like, there’s a lot of water. There’s a lot of ocean. But even seeing what Venice breakwater looks like here after the pandemic, in the summer, when all the schools come out, and it’s just tens and tens of people that are surfing very, very closely together.

That’s not even the lineup. It just becomes dangerous, if anything else. And then they’ve closed the, there’s only a certain section that is open because of the swimmers.

Matt: You can see pictures from the 60s where it is not a new problem. You can see pictures of Manhattan Pier from 1963 or Huntington Pier, and it’s just dense with surfers. And furthermore, they’re all riding 25-pound boards, not seven-pound boards.

So it’s not a new thing, and complaining about it’s certainly not new. And I just hit a point where I would decide I was gonna go find a lesser quality wave and not bother with this, and just go find something else. Because I’ve also done it the other way, too, where I’ve gone out there.

I never fought anybody, and I never really yelled at people, but I was always looking to be friends with the guys who would threaten other people. Like, I always wanted to be under the, you know, that’s the kind of coward, that’s the kind of, because I’ve never been in a fight. It’s very strategic.

I’ve never been in a fight in my life, but if I can charm somebody and be friends with the guy who’s the muscle guy, and I actually had that times in San Francisco where I would mouth off to somebody or somebody would mouth off to me, and I would snap back because I know that, if I have to, I could just yell down. So it was, you know, it’s funny when I think back. Again, I very much think of my active surf life as being over, and when I surf now, it’s just to sort of put me back a little bit of a reminder of what it was like.

When I think back on this sort of active surf life about, that I had for 40 years, how much of it was so much, what you say, strategic. Some of it, all we were thinking about when you’re fantasizing is how to fix this turn, you know, what time should I leave to make sure, but you’re thinking about the moments you’re riding well, but you’re also thinking all the time about where do I put myself in the lineup? Who am I talking with? Who am I not talking with? You know, how am I gonna change this year’s boards compared to last year’s? And how many, you know, all that just constant checking on, checking the gear. How’s the, you know, is the fitness right? Is the work schedule set up right? All of that planning and all of that strategizing and all of that stuff that you’re doing on the fly too, like I remember being in a lineup if it’s crowded and if people are just sort of talking and there’s a lull and you notice before anybody else does it, there’s a very slight drift and you can just go over there.

So if you’re really on top of it, you can, you know, do all that stuff. And I thought by the time I was ready to step away from it, I was so glad to let it all go because it’s a lot of time and a lot of, you’re just running, you’re running calculations nonstop. I was anyway, you know, to do this.

And to be honest with you, you know, being in a better mood or smiling more was never ever part of it. No, which just doesn’t sound like a lot of fun. It sounds extremely strategic and it sounds like work.

I never said surfing was fun. I think it’s, I think what surfing is, is absolutely addictive and compelling. And it was like a project.

It was like a project or maybe even some kind of very difficult game where there’s level to level to level, it was never fun. And it was very, very rarely that I feel satisfied with it. But if I did get to that place now and then, then that was the best I’ve ever felt in my life.

So every now and then, if I was, it usually didn’t happen until I was pretty close to exhaustion because I’d never surfed well until I was really tired. Because otherwise I would be, I was always in my head too much. I was, I would be self-critical or I would be thinking I didn’t do that right.

And if I got tired enough, but I was limber enough and I had enough adrenaline in me still, like if I’d surf for six hours and the waves were getting better, I could sometimes find, I could find finally, just barely, I could just touch the bottom of that sort of flow state. And I remember a few times where I was there mindless, didn’t matter so much how I was surfing. I was just, you know, and I usually would end up surfing.

That was the best I could surf. But you know, that was really rewarding, but I enjoyed all the stuff we’ve just talked about. I enjoyed sitting down and going, okay, I’m gonna get four new boards from Pat Ross and how I got, I guess, and I would just take, you know, one evening for each board and design them and then call up Pat and say, here’s the four boards I want this year.

And then, you know, I get the boards and I was a whole thing about testing them all. And then I’m gonna get rid of these two and I’ve got to replace these two. And then, you know, I liked, it was like a job, like you say, it was a job that I just loved.

And it’s the same exact thing that I’ve done with encyclopedia surfing. So that’s, you know, that’s hours and hour, 10 hours a day of my life. And a lot of it is really on, is just doing data entry.

A lot of it is just filling in, you know, doing metadata. A lot of it is just editing a clip so everything fits right. But, you know, if at the end, if something comes together the way I’ve tried to sort of do it, there it is.

And then that’s just, that’s the sort of not enlightenment, but that’s the thing that I aim for. And if it’s a few seconds long, it’ll resonate with me for a while longer. And the best moments I had surfing for sure resonated, but you could go weeks or months without feeling that, but it also didn’t matter.

If I didn’t get to that place, it’s still like, I always felt wonderful driving home. After surfing, I felt amazing. You know, just because of the physical part of it.

And now that I, you know, now that I’m 65 and all I’m doing now, because I’m just creaky is getting steps in to stay, keep my weight down a little bit. You know, it’s funny, because when I was surfing all the time, because of all that strategizing and tactical sort of planning, I was also eating better than I’ve ever eaten. And I was also working out more and I was running more.

And I was like 28, I didn’t need to do that shit. I was already surfing six hours a day, you know, but I was doing everything I could because that was the thing I wanted to do. And it all felt, I don’t know, it all felt righteous.

It all felt like I was, you know, looking back, it just goes, it’s insane. All I was doing was surfing. There’s nothing, there’s no point to it.

It was just this, but I felt like I was some kind of, you know, on some kind of weird religious sect or something or some order, like some kind of samurai. That’s how it feels to you when you’re in the moment of it. And again, looking back on it now, wow, I pissed away all those years just doing this one thing and I could have been traveling somewhere.

I could have been trying other things. Nope, I just bore down on this one thing. And it’s, you know, I still struggle.

Do I regret having spent all that time doing it? I suppose that ultimately I do not, but it was only because I kind of pulled it off at the very end. I got married at, I got married at 45 and I had a kid when I was 49 or something. And, you know, I barely got out of there without getting stuck in it forever and permanently.

Because, you know, it’s hard, if you get that deep into it the way I was, it kind of gets harder and harder to get out of it.

Campbell: So. The book I’m reading just now is William Finnegan, Barbarian Days.

I haven’t finished it. He gets into that sort of thing. And there’s a, he must be in his mid to late 20s by that point, and he’s wondering if this is what he should be doing with his life.

Matt: So he was the guy in San Francisco hanging out with Mark Reniker just before I arrived. So I arrived up there when I was 30 and Bill had just moved out about three. So that book, Barbarian Days, started as this two-piece article in the New Yorker, in I think 91 or two, called Playing Docs Games.

Doc is Mark Reniker, who was Bill’s like spirit animal when he first arrived in San Francisco. Because Mark Reniker had been there forever and Mark said to Bill, okay, you’re here, great, welcome. We’re gonna surf these days, we’re gonna go to these spots, I’m gonna set you up.

And Mark loves being the person who guides you through your experience as a surfer in San Francisco. He did that for Bill. And Mark Reniker is another really charismatic person who Bill fell under Mark’s spell.

And then, do you want me to talk, can I talk about the book? I don’t want to spoil it, I don’t want to spoil it. I’ve just hit the San Francisco bit, but that’s okay. I don’t want to, do you want to leave while I spoil it for you?

Campbell: No, no, no, just spoil it away.

So he finally decides he doesn’t want to be Mark Reniker’s running partner. He wants to go to New York and become a writer, and he does. That’s so, in other words, the book, or the essay, Playing Doc’s Games, sort of ends with Bill’s deciding, I’m not gonna stay here and keep being a surfer, living the life of a surfer.

I’m gonna go to New York instead and try my luck as a, he was already a writer, but he’s gonna really commit to being a writer. And as we all know, he pulled it off. And now he’s got a, he won a National Book Award, ironically enough, on a book about surfing, you know.

But I ended up going up there and becoming Mark’s, I was like the replacement person for Mark after Bill had left. Mark had a, Mark kind of collected us. You know, Mark was this guy up on the third story of this building that overlooked this break that we all went to, Terraville Street.

And Mark would stand up there with a towel around his shoulders, looking out the waves, this big beard, and he would yell down, it’s getting battery, guys, it’s getting, and we’d all be down there going, oh, what, you know, and what’s the report say? And, you know, and then eventually when Mark put his suit on and come down, we’d all kind of follow him in the water and stuff. but Bill was super, Bill was absolutely as caught up in it as I was. And I think Bill would sort of say the same thing, that it wasn’t fun for him.

It just becomes this thing that you’re, that you’re, this project, it’s like a big project that you’re working on. And I wouldn’t have wanted to, I didn’t want to do anything else but work on that project. So when did you make that decision that you want to like step away from having surf as your work and then make writing about surfing as your job? There was a few years where I could see that it wasn’t going as well as it had.

So I moved to, you know, I was the editor at Surfer Magazine, I worked at Surfer from 85 to the end of 1990. And at the end, the last few months in 1990, they made me editor, even though I really knew at that point that I didn’t want to be doing that anymore. I wanted to go back to school.

I dropped out of college. So I thought I was leaving surfing at the end of 1990 when I went up to UC Berkeley to finish school. I quit, I quit being the editor at Surfer.

I sold this beautiful house that I’d bought in San Clemente and went up to Oakland to go back to school as a, you know, a junior transfer. I was a 30 year old undergrad. And that was gonna be my thing.

I wasn’t thinking about what the future was gonna be. I was just gonna go back and be a student. And I loved it.

I loved taking all those 101s that I’d missed out on. I studied Japan, I studied art history, I studied all these different things, got a degree in history. But meanwhile, because I wasn’t working a job, I’d sold my house and I had some money, you know, there was plenty of time to surf.

And Mark Renicker, the guy I was just talking about, had me on speed dial and he was calling me every day. And I got up there, I went, I got up there in, right after day after like, right after Christmas, or maybe New Year’s. I got up there like January 91.

And the season, you know, the surf season, it’d been going for a few weeks, but it was just an, I got up there just at the beginning of like a two week. So in San Francisco, you’ve been up there enough. Like it’ll sometimes if a high pressure will hit, it’ll just, the wind will blow offshore for days and days and days.

And that’s what it did. And so, you know, my big surf, my big getaway from Surfer Magazine puts me right in this place where I was riding the biggest, best beach break waves I’d ever seen. And suddenly I’m right back into surfing.

Not only that, in fact, I’ve got a whole new lease on it because now for the first time I was riding bigger waves. So I was taking these little, taking these classes that I was doing well in and loving, driving across the bridge, sometimes twice a day to surf. And that sort of got me, kept me into the surf game for another 20 or so years.

But in my, right around when I turned 40, I was just, it was, I could see it was sort of running out of steam a bit, but the momentum was so massive at that point that I just sort of kept going. My brother had gotten married. I had a niece who I adored and, you know, I was absolutely as comfortable as anyone could be living by themselves and kind of until I wasn’t, you know.

And then, you know, I just see how fast I can make this, all kinds of bad decisions and choices with who I was dating and who I was living with. Finally was introduced to my woman who I married to now, Jodie Davis, at that point, and I think that was in 2003. And we married in 2005 and Teddy was born in 2009.

And even then, even with a one-year-old son, and I was just about 50 years old, I think I was 50 years old, Jodie got a job offer at Amazon. She was working at the Chronicle Books. And even then, the money was so good and the offer was amazing and it would have solved just so many problems for us.

And I’m going, I can’t go, you know, I’m so sorry. I guess we’ll have to make it work from, you know, some kind of commuting, just way up on my high horse because I couldn’t leave surfing and everyone knew that, dah, dah, dah. And she was super bummed, you know, she should have been because this was her big, it was a great career move for her.

My wife comes from, you know, she was a, worked for a literary magazine in New York. She was working with Gordon Lish at his magazine. He came from hardcore, you know, creative writing, all this, and that’s what she wanted to do.

But she was also way more realistic than I and the amount of money they were dangling in front of her was stupid to not take it. And here I was, hey, I can’t go because I surf, you know. And my dad has always been my sounding board and my number one source of advice.

And I called him knowing that he would, and he’s been in LA his whole life. He’s still in Culver City. And I called him saying, you know, just knowing that he was gonna back me up on this because he understood that, you know, you are where you live kind of thing.

And I’m laying this all on him for the purpose of him supporting me in my decision that I made. And very politely, to his credit, you know, he said, well, let’s think about this. And then within 30 minutes, he had convinced me that this was the time to, this was my, it wasn’t quite as clear as I’m making it sound this was my exit.

And not only was it my exit, it’s the right thing to do for your family. And I, you know, so I’m on the phone. Just that morning, I woke up, Jodi had spent the night on the couch.

It was a whole horrible scene. Or I spent the night on the couch somehow. She’d gone to work basically, you know, having dry, she was crying and the whole thing was such a big mess.

And I was, again, I was just firmly convinced that, you know, hey, man, you know, you knew me when you married me. This is what I do, blah, blah, blah. And my dad turned me around really quickly.

And I think he turned me around quickly because some big part of me knew that it was time to not surf. And I called up Jodi and I said, hey, I’m gonna come down and talk. And I met her out in front of Chronicle in San Francisco.

And I said, look, we should go. You were right, I was totally wrong. And she didn’t believe me.

How could you change your mind? And I said, well, look, she knew that my dad was, I said, I’ve had this long talk with my dad. I also just think that this was the right thing to do. You’re right, he’s right.

Let’s do it. So long-winded way of answering. If I was gonna put a moment on when I took this off-ramp, it was when I was exactly, I think, 50 years old when we moved to Seattle.

And, you know, we moved to Seattle and there hasn’t, I’ve surfed since then, but that was the last, the day we got on the plane was the last day that I woke up where waves were gonna determine what my day was gonna be like. And, you know, and it was a little bit, it was harder being in a new neighborhood because it’s hard to move, you know? And I was old and I’d been in the Bay Area. I’d been in San Francisco for 20 years.

I knew I had an auto mechanic who I adored. I’d been going to the same dentist, the same everything. And so having to figure out all that new stuff again was difficult.

That was more difficult, I think, than not surrendering to surfing every day. I was, part of me, even from the beginning was relieved. It’s not, and I didn’t wanna have to keep being, I was such a good surfer for so long.

I didn’t wanna keep having to be a good surfer. I didn’t wanna have to keep thinking I gotta go out and impress myself or impress somebody else. I’m still doing that.

I can’t get over doing it because I was, from age eight or nine, I was always going out there and people were saying, wow, you’re a good surfer. And I, you know, and that’s just baked into me that I’m supposed to be that person. And that’s not a healthy way to surf, you know? You’d rather just go out and have fun.

And so I didn’t have fun surfing unless I was surfing really, really, really well. So that came, you know, once that collapsed, it was my interest in actually riding waves kind of went with it. But that was fine.

That was a great new, it’s been a fantastic new chapter. It’s been me working on, and I think of working on EOS, the site, even though it’s about surfing, because that’s what I know about. It seems almost divorced entirely from the kind of surfing we talked about where I’m, even though I’m working on EOS with that same kind of slightly insane focus and strategic sort of thoughtfulness, and it’s gotta be done.

It’s gotta be done just right. That’s the way I used to surf. The fact that the thing I’m doing, this project I’m working on is about surfing.

Of course it is, because that’s where I learned to write. From writing about surfing, I was the editor at Surfer Magazine. It makes sense, but I really feel like this could be about birding, or it could be about, it’s kind of like the thing that matters is that I’ve got a project that I get to work on every day.

That’s not entirely, I’m being a little bit too glib, because there are times every day, or at least a few times a week, where I’m working on something that almost, without meaning to, will strike a memory that will take me back to something that happened from all those 40 years. So the work does get me back to who I was as a surfer, and it makes me feel like that was all worthwhile. So it does do that.

If I was writing about birding, it wouldn’t. And I could write about birding right now, because we have two eagles in our neighborhood that are setting up a nest. Two blocks from my house, these two eagles, male and female, and they were there last year, are doing their nest again.

And I’m out there with Teddy and Jodi going, the eagles are back, the mother’s back, she’s sitting on the nest, so I get all excited about this sort of stuff. So I kind of get where that comes from. But I couldn’t actually be writing about birding.

But anyway, that’s where I’m at, and I’m going surfing next week. You are? Where are you gonna go? I’m going back down to Pavones in Costa Rica, near Pavones. Not Pavones, near Pavones.

And I went last year, and again, I think that if I’m lucky again, it’s the same thing. It’s so hard to be, basically I’m a low intermediate surfer now.

Zuz: I was going to ask you how you think about yourself.

It’s like, are you an advanced surfer?

Matt: Well, in my day, I was a beyond advanced surfer. I was an incredibly good surfer. I was a world-ranked surfer.

But, you know, what I am now is if, if I can get into a wave early enough, and I can get my feet underneath me, and I can get a little bit of rhythm going, then somebody would stand on there going, look at that old guy, he’s still got it.

Zuz: Have you ever Googled yourself?

Matt: Yeah, yeah, I don’t know, yeah.

Zuz: Yeah, where I’m going with this is, if you Google yourself, at least when I Google you, you come up as Matt Warshaw, former surfer.

Not even former pro surfer, just former surfer, which I find absolutely hilarious.

Matt: That’s a little bit insulting.

Zuz: I know it is, isn’t it?

Matt: It doesn’t even say like surf rider, right?

Zuz: No, no, it just like, we can do it now.

Matt: No, I believe you.

Zuz: Yeah, I was so surprised. I thought, oh no, they definitely mean pro surfer, but.

Matt: The pro surfing part didn’t last very long, and even though I’m proud to say that I had a ranking at one point, it all just came down to me.

Zuz: Here you go, former surfer. I wonder, I mean, obviously, it’s some kind of algorithm thing, right? I think it must be something from the AI snippet.

Matt: Yeah, yeah. That is just pulling it, but it’s. I guess it’s better than being a former human, you know, I’m still a former person.

Zuz: So how many hours a day do you work on the encyclopedia?

Matt: Um, eight to 12, maybe, or something like that.

Zuz: You’re putting more hours than I do. And I steal a lot of stuff from you, obviously, whenever I write my history.

Matt: I steal stuff from myself now, because I’m forgetting what I wrote. So I’ve actually gotten to places where I’ve read blocks of texts going, jeez, look at this. And I go, oh, I wrote that 15 years ago.

So it’s great. Maybe because my memory is going, but I’ve gotten to a point now where I can impress my own self with my own writing, because I haven’t, I forget what I’ve done. And if I’m in the right mood, and I go, oh, that’s pretty good.

Zuz: Have you ever listened to History of Surfing as an audiobook?

Matt: No.

Zuz: Oh, you should.

Matt: Yeah, somebody else said it’s good.

Who did the reading on it? Who knows, right?

Zuz: Paul Boehmer Oh, you see, I wanted to ask you about this, because I thought that maybe you chose him. Because when I started listening to it, I just, I was like, this is really weird.

He’s got a very distinctive voice. It’s very measured, and it’s, to some part, it doesn’t even sound human. He’s a trained actor.

He was like in Star Trek and everything else. But it’s very, very unique. So that’s not what I expected.

But the more I got into it.

Matt: I wonder when they made that book. I wonder when they did it.

Zuz: It sounds great. It’s funny.

Matt: As a rule, anything, anytime I finish something, so when I finish a Sunday joint, or when I finish a book, or when I finish, I just drop it, and I can’t even, like, so I finished History of Surfing.

I was so happy with how the cover looked. I was so happy with the photos that got picked. I was so happy with that book cover to cover.

And this, I swear this sounds like something that I’ve done retrospectively. But I said, that’s the last book I’m gonna write. And I think I may have known at some point that I was going to go back and do something with Encyclopedia of Surfing.

But I also realized, I’ve written a History of Surfing. Like, I’m not gonna go, I don’t wanna. And I was so happy to basically say, that’s the last one.

And it was the last one I’ve done. You know, and I, I don’t take full credit. Like, that book ended up in so many, like, photo shoots off on someone’s coffee table.

Zuz: It’s a beautiful book.

Right? Like, the goats are sitting there. Yeah, it’s always, it would turn up all over the place.

And like, I remember somebody sent me a thing saying, oh, look in, you know, Women’s Something Magazine, 10 Things I Can’t Do Without, number seven. And Matt Ward said, you know, and just, it was just, it was just like, it became this item that, and that wasn’t my doing. That was just, the designer on that book was great.

And it just came out right. And it, they made my name so big on the cover. Like it says, history of surfing in whatever massive font that is.

And then in an equally massive font at the bottom in equally bright red letters is my name. And part of me just going, well, I’m never gonna, also never gonna get a credit like that again. So I, and all the books I’d done before that, most of them were either somewhat or really badly sort of flawed in the design or the edit didn’t get done right.

And it’s so hard to get a book done. And I had all this, I had all this power. I’d just done Encyclopedia of Surfing.

And when I signed up to do history, they basically let me, they basically allowed me to pick who I wanted to work with and all that. And it came together so well. And I worked with an editor who I adore.

And I didn’t even wanna try to replicate that experience. So I thought, I’ll go do something else. And that was when I really got into deciding that I wanted to do the Encyclopedia of Surfing website, which I didn’t know anything about.

And I don’t think I would have done it if I did know about it. Cause I had to teach myself, you know, as I went. And it’s only in the last three or four years, 16 or 17 years later that I sort of got it sorted out.

And if I, again, if I had known anything, I wouldn’t have done it. So there’s a case, I don’t know, I wouldn’t, I would never. People seem to think that I’ve made this weird career that had so much to do with having parents that supported me even when I was a full-grown adult, having a wife that supported me when she was making money.

And one of, a part of the, so before, when Jodi and I were still discussing the Amazon move before I had given a definite no, she had said, let’s take this money. You can go up there. You don’t have to do any freelance work.

You can just take two years, not work and set up the Encyclopedia of Surfing. And so partly, you know, when my dad was saying this might be a good opportunity, part of me was going, shit, that’s right. I can just go up there and not work for two years and work on the, not work, but I mean, do the website.

So I like, what I’m trying to say is people have asked me for career advice and I have nothing to say to any of them because so much of this was just good luck or me being slightly scheming and, you know, at one point, 30 years ago, my dad married a woman who was wealthy enough to sort of support me when I was writing for Surfer’s Journal. And like, you know, I was just getting, I was just getting like this subsidy, even though I was a grown ass man. So what am I supposed to say to someone who’s a teenager saying, wow, I really admire your career.

You’ve been, or you’ve been so true to what you believe in. I’m just thinking, like, of course I am because I didn’t have to do what everybody else has to do. I actually, you know, so I’ve steered more people away from surf riding than, you know, and people who have ended up being really grateful to me saying, I just did it on the weekends or something.

And I forgot where I, I forgot how we got started off on that topic, but it’s not, it’s a pretty, been a pretty weird career and it looks a lot, it looks nobler. I get to pretend that it’s sort of been a noble career or that I’ve done it for the right reasons or it’s been sort of, I’ve passed the purity test on it. And man, you know, it was just living on the good grace of other people, so much of it.

And here we are doing this podcast.

Zuz: But listen, we’re benefiting from it. So we’re grateful to everybody who supported you.

Matt: I tell myself that, that I wasn’t just, I wasn’t just sitting down. I was really trying to do something to just to, I was trying to do something to make this not feel like I was ripping everybody off, you know? So I am happy with, I’m really happy with the work, but it, you know, it was, it all feels fortunate and it definitely feels like it was something that was gifted to me to some degree. And, you know, you’d never be able to repeat it.

It was, I was good at taking, I suppose, I suppose I was good at seeing what the next step would be. And I was always good if there was something dangling, it was some advantage dangling in front of me, I knew how to go grab it. I remember somebody saying that there was a possibility that somebody at Interview Magazine wanted to do a surf piece, you know, Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine.

And this would have been in like 1987 or 88. And I found out the name of the person, made contact with him and flew out there to see him just based on the possibility that I might get the gig, and I got it. So like I did go after, I definitely know how to go after something.

I bought a new suit that I thought was cool because I was going to New York, I hadn’t been in years. And I knew that this guy liked 15th century church music. Somehow I knew that he had, and I showed up with this CD of someone I knew he liked, like I could do that, I could sort of woo somebody.

And I knew how to get people to work with me on EOS. I got everybody who, everybody, the thing about EOS that nobody really comments on and is the biggest miracle of that whole site is that I got all these famous filmmakers and photographers to agree to let me use their work for no charge. Otherwise there wouldn’t be a site.

The whole point of EOS is that I was, the book version of EOS existed, and it was great as far as it went. It was great as a big, giant, brick, thick thing of text. There’s no photos, there’s very few little black and white photos in it.

But if you’re doing a surf work, you know, and putting, and there’s no images in it, and there’s no color, and there’s no film, you’ve kind of left the, you’ve left a lot on the table, right? And so in a way what EOS started off as, the website, was going back and finishing the job with photos and film. And it was a little bit hit or miss, it was a little bit touch and go at the beginning because I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to get all these people, many of them who I knew, to be able to say, who all of whom were really, most of whom were just vicious if you used their thing without permission online. And I got them to let me use the stuff for no charge.

And there was a really famous photographer named Art Brewer, who you guys might remember, he died a few years ago. He was, you know, if you’re gonna do some kind of, you know, Mount Rushmore of surf photographers, if it was, how many people on Rushmore, four or five? Four, I think. He’d be one of the four, you know, he’s one of those figures who’s, and he’s as good, as talented as he was, he was also just as mercurial.

And sometimes we got along great and sometimes he would be, and he was an enormous man, he was terrifying. And he liked, you know, even though at this point, I was in my 50s and he was 10 years older than me, he always thought of me as a kid because when he got, when I got to surfer when I was 25, he was, you know, the Dean of the surf photographer. He was the big cheese and he didn’t even talk to me for five years, I was always this punk ass kid.

And at some point when I was a surfer, I did an article that he hated and he called me on the phone and just yelled at me for it and I had to just take it. And then we made up and then when I was starting to do Encyclopedia of Surfing online, I got Jeff Devine to say I could use his stuff, another famous photographer, but he, Jeff was easy, he’s a big, cuddly person who adores me. But I knew I had to get Art on side, Art Brewer, and that took me months of calling him and saying, and at some point he just said, you know, I don’t think this isn’t gonna work.

And I just go, okay, fuck you, Art. I mean, you know, I just snapped me and it wasn’t quite that, and at some point I snapped and said, you know what, fuck you, I’ll do it anyway. And he goes, I’m just kidding you, Warshaw, you can have it.

And he’s just toying with me, he said, you can have it, take whatever, he goes, take whatever you want, I’ve always thought your work was great. And he just turned a corner and from that point forward, and so what happened from that, I was able to call up all the other people that I’ve been waiting for and to say, Art’s on board, Jeff’s on board, Bruce Brown’s on board, then they all fell into place, but it didn’t all, but most of it went down to getting Art Brewer on board and it took me months to get that done. But that was the biggest, like the biggest trick of Encyclopedia of Surfing, so if you go look at it, you know, it’s just this, you go onto the homepage, it’s this grid of images.

Zuz: They’re gorgeous.

Matt: Yeah, and that’s, I love that grid and I’m, you know, I did long, I didn’t invent this grid, but it works, every grid you click will take you somewhere.

Zuz: Oh, I didn’t know that.

Absolutely, every one of those things will take you somewhere and you know, I don’t know, you know, every 10th image on that grid is probably one of Art Brewer’s and every, you know, half of those images are people that came on board because Art came on board and if I get to go to people and say, Art’s doing it and Bruce Brown also came on early and so that was the big, that was kind of the, it wasn’t a miracle at all. I worked really hard to get those people on board and then some people, at some point, after enough people came on board, I didn’t even check with them. I just thought, I mean, I’m just gonna go and use their stuff and if they complain, I’ll say Art, but you know, that was something, I’m proud of that.

Zuz: So I know I promised you that we’re not gonna talk about history of surfing, that this is gonna be a Matt Forward episode, but I’ve got one question, actually, I’ve got two, but my first question is, was there ever something that you’ve discovered and you just kind of went down the rabbit hole?

Matt: Every week. No, no, really, it’s like, because I’m trying to think of an example. So I did a piece on a famous, not famous enough, Malibu surfer named Vicki Flaxman, Vicki Williams, who was sort of the best female surfer.

This is all pre-Gidget by about five years. Everyone thinks Gidget was the first surfer at Malibu and she went, not only wasn’t the first, she was like, you know, these group of women that surfed there before her were all better, they were all more into it than Gidget. Gidget was just sort of there for two summers or something.

Zuz: She used to babysit our neighbor. The lady who inspired Gidget used to babysit our neighbor when they lived in Brentwood.

Matt: She’s a trip.

But Vicki Flaxman was there on the beach at 16 with her other 16 year old friends and then the local hot surfers, Matt Kivlin and Tommy Zahn and Joe Quigg, you know, met them and made them boards and off they all went on these boards that those guys made that were called the girl boards because they had to make the girls needed boards that were gonna be smaller and lighter so they’re little 16 year old arms. You guys probably already know this story and then, you know, in the afternoon, somebody would, the surf would be kind of blown out. Oh, I’m gonna take out, I’ll take out Vicki’s board because they wanna go out and just mess around on a smaller, lighter board.

And in the morning, you know, the boy surfers are all just sort of going along in formation, riding fast and then in the afternoon, when they’re borrowing the girl boards, they’re able to sort of go more like this. And then suddenly one of the guys, the hot, the most athletic of those men surfers named Les Williams did a turn back into the wave and kept going. That was like the first, did the first cut back on one of those girl boards.

And then the next thing you know, they’re not giving the boards back. And so those boards that were made for the girls, for Vicki and Aggie and all the other became the model for the boards that got us to the surfing that people were doing up. So once I started, once I, you know, Vicki Flaxman’s still alive and I got her on the phone, her EOS page was needing some upgrade or something or somehow and I got on the phone with her and she was so fun to talk with and she had so many stories and she was so catty about all these women that she had grown up with, Gidget included, not in a mean way, just in a way like you’re going, oh my God, she’s 94 and she still absolutely remembers that so-and-so, this woman surfer cut her off and like, and she was just laughing at all this and she was loving, remembering and she was going, we were so stupid and she was saying, we had so much fun, we were so drunk, the surf was so good and she was telling me all these stories and you know, and she went to the, she went to Samo High or maybe she went to Pali High or something and she was telling me about the cars that she drove and you know, and next thing I know, I’m down, I’m trying to find out what, you know, who was at Samo High at that point and what cars were they driving and when did Mal, and you, so to make her story more interesting or whatever, you know, you wanna go find out about, because the surfing part of it, when you, if you remove it from everything else that’s happening, which is what the surf magazines did for so long, if it’s just the waves that we’ve ridden and the people that we’re talking about surfing with, it’s not as interesting as when it’s all rubbed up against or enmeshed with, you know, what music was being played, what cars are we driving, where are we getting, where are we going afterwards, what clubs are we going to afterwards? And so, you know, you wanna start, and because I’m from Venice and surf Malibu, it was so much fun for me to just remember or look into what would it have been like to have been a surfer in 1949 or 1950 when Vicky was down there.

And looking at these photos of her and looking close enough to realize that she was drinking, you know, Three Roses wine, and that was at the wine, or something like that, or Five Roses or whatever it was. And so, and by, and so it’s just fun to go down those rabbit holes, but then I always find that if I’m writing the Sunday Join or if I’m writing a thing on Vicky, if I, you can take some little fragment, you can take 2% of what you just learned going in that thing and just sort of stick it in there somewhere, and it makes the writing better. And it makes, if the writing’s good, then I’m pleased with myself.

And the person who’s reading it isn’t getting the usual canned history if they find out that she was on the beach drinking Three Roses or Five Roses or whatever it was, and that she was driving a, you know, a 42 LaSalle or whatever it was. It’s just, then it becomes, I feel like you’ve done the job, then you’ve done the job right. And it does make, it does, like, it gets me back to feeling like I’m kind of honoring surfing in a way, not honoring it, but I’m doing, I’m servicing it in a way like, it wasn’t just these kids out riding waves, they were also part of this cultural thing.

There was also part of this school thing and some of them went on to do this and some went on to do that, and they were all at the beach this one time and they all kind of went different ways. And how did Bob Simmons fit into that? And how did he not fit into all that? And, you know, and it was just, I just can’t help but wanna put, I wanna make her, I wanna make Vicky a full character, not just the woman who surfed great. And I wanna also make surfing more interesting because it didn’t exist in a vacuum at Malibu.

It existed as something that certain people went out and did, and then they came back and then they had their lives and then went back out and did it again. Some of them went on to become architects, some of them went on to shape surfboards. And the idea of living a surfing life becomes for me, and it always seems like it’s sort of self-justifying, but it becomes more worthy when it all plugs back into something that’s still, that’s happening where it’s not just shutting off the world and going surfing, where it’s something that you occasionally veer off from the world, surf and come back and re-engage to this day.

Well, I think bringing in all these details that what actually brings it to life, we can actually visualize it. Otherwise it would be just a girl on the beach and just surfing, that’s it. That’s right, yeah.

Zuz: So I ran a little experiment. I wanted to find out whether surfers today actually think, knowing things about history of surfing and surf culture matters.

Matt: Well, you told me this, you asked and they still said no.

Zuz: So yeah, so on Reddit, on Reddit in the beginners sub, I got like, first of all, it was like, no, I just want to go out and surf. And then when I tried it in the main surfing thread, where it’s more like advanced surfers, I got some good responses that people did care, and then I got shut down because you’re not allowed to source your ideas for podcasts on that specific sub. So I was put right, kicked out.

But when I asked in my group, they all said, yes, it is important. And yes, these are the books that we’re reading. And we want to know about history of surfing from like the ancient Hawaiians and it’s important not to whitewash it.

And it made me feel so much better.

Matt: I’m glad, I’m glad to hear that.

Zuz: Do you think it’s important for like surfers, people who go out into the surf to know and care?

Matt: I don’t know, it’s a funny, I get hung up on the word important because when I think about, I get caught up in sort of the semantics of, is it important? It’s not important in the least.

Like it doesn’t like, I don’t mean to, there’s so many things that matter more. I think what does make sense to me that is bigger than what people talk about usually with surfing is, surfing is, I do really think it’s its own thing. It’s very unique and it ought to be sort of talked about and framed as this thing that is not, it’s not an Olympic sport.

It’s not even a competition really. You can take it out of its sort of natural environment and if you force it hard enough, you can fit this round thing into, or the square thing into a round peg or whatever the other way around. You can make it a sport.

You can put people in jerseys and have them paddle out and score that. You can do all that, but the idea, there’s something about sort of being invested in or setting your sort of internal clock by or just you’re setting your life by weather conditions, wind, swell, all of this and sort of having to constantly be paying attention to that and trying to figure out how to put yourself in a place where you can mingle with it in a way that we all love. And there’s definitely something about just how amazing it is to just basically strip down at the beach, leave all your clothes and your watch and your keys here and enter the water, like the dividing line of the beach, dry here, wet here, solid here, liquid here.

That’s a pretty weird thing. And if not, where’s the wrong word? It’s really unique. And so I really enjoy thinking about or presenting, I don’t necessarily, I don’t talk directly to all that, but the people that sort of locked into surfing and had to figure out like, what is it about it? Like why, what is it about it that attracted certain people and how different is surfing from these other things that we do? Like I love trying to sort of place, I love trying to sort of get at from weird little angles that the fact that surfing is unique, different, special, I guess.

Then even skiing, my son skis and I go up with him all the time to drop him off and I’m standing there partly wishing that I could go up there and still ski with him. I can, I could, but I don’t wanna, but also thinking, partly thinking, God, this is so lame compared to surfing, like watching him go up and down. It’s just like, you’re gonna stand in line with everybody and you gotta listen to that shitty music that they’re playing at the bottom of the lift and you only get to ski down kind of this part of it.