Now Reading: How on earth do we measure waves?

-

01

How on earth do we measure waves?

How on earth do we measure waves?

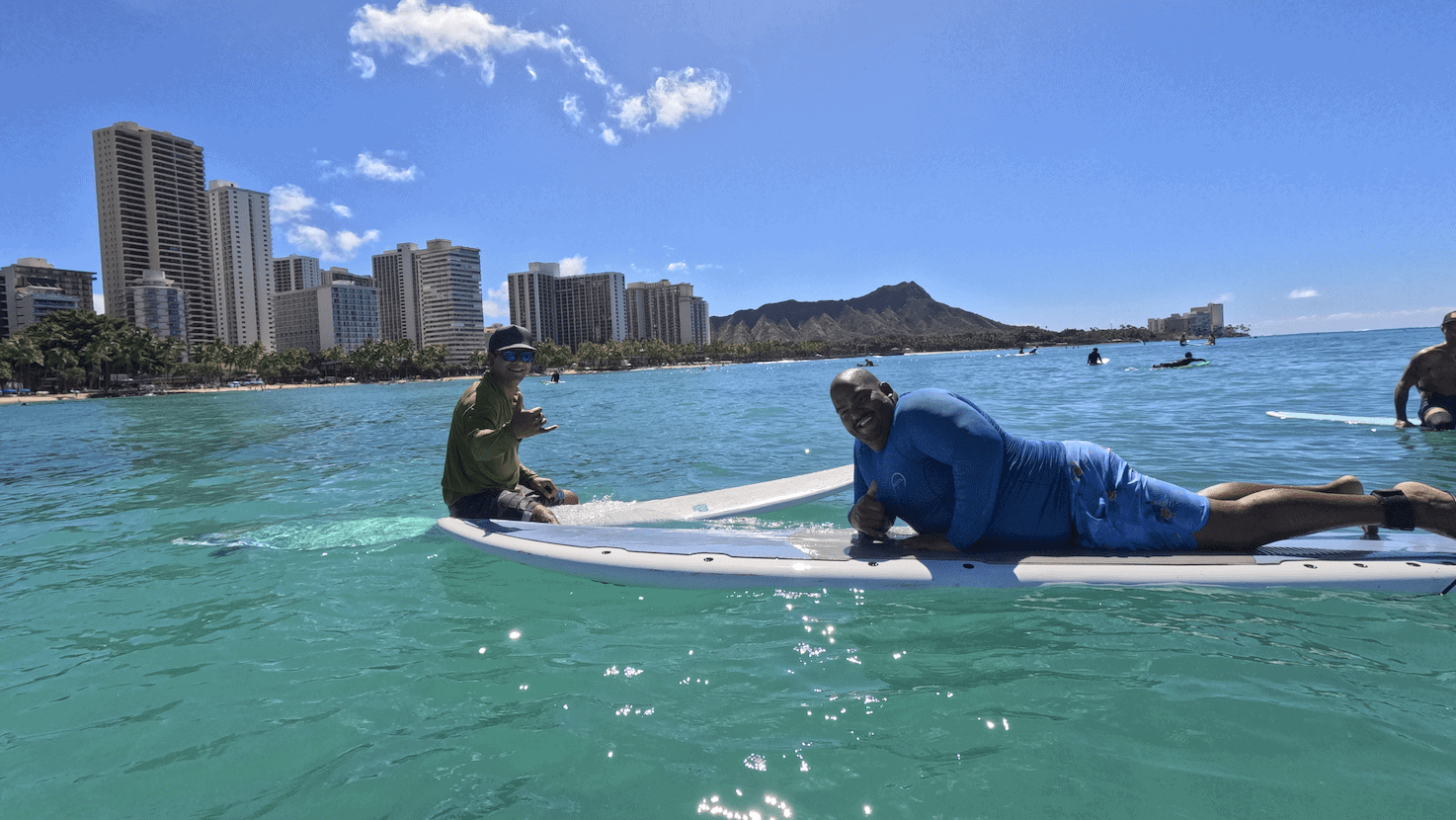

Let’s talk about measuring waves. And if you think that’s boring, think twice, because people’s livelihood and pride are on the line.

No way it was a 100‑foot wave! Surfline lies! It said it was going to be 1–2 ft and it was 3–4 ft! “40 feet!” “No, honey, 20 feet Hawaiian!” Seriously, we can send a rover to collect samples on a distant planet, and yet we still can’t measure waves accurately.

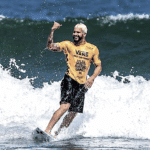

I know I’m late to the party, but I’ve been watching Garrett McNamara’s 100 Foot Wave, and the guys answered one of my pressing questions. Namely, how the fuck do you measure the size of a gigantic wave like Nazaré.

What the big wave folks say

It’s complex yet simple according to Bill Sharp, founder of the Big Wave Challenge: “What you’ve got to understand is that measuring a wave is very different from measuring a mountain. A mountain’s not gonna move. You can go back and measure today, you can measure tomorrow, you measure it next week. The wave is only there for that fraction of a second. And there’s nothing you can ever do to bring it back.” No shit, Sherlock.

CJ Macias, Garrett McNamara’s brother‑in‑law who surfs Nazaré, explained it in more detail: “One takes the best photo image of a wave, and decides where the bottom of the wave is and where the top of the wave is. Then, taking a guy who’s on the wave surfing it, and guesstimating how tall he’s standing in the photo—’cause remember, he’s crouched down as low as he can be. And then, literally, placing him from the bottom to the top, counting as many times as you can, multiply by the supposed height of the surfer, and you have the size of the wave.”

This is similar to a traditional marine estimation method onboard boats: the “height of eye” method, comparing a wave to the horizon or to known structures from the trough.

Accurate? Not even close.

Accurate, it ain’t. But I’m learning that measuring waves is subjective, because it’s impossible to get the accuracy within a foot… can you? It’s being tried, especially when it comes to measuring world‑record waves, and now even drone footage is involved.

There are other methods like buoys, pressure sensors, and satellite altimetry, but they’re far more useful for forecasts than measuring one specific individual wave.

What we can agree on

One thing we can all agree on is that, in oceanography, wave height is defined as the vertical distance between the crest (top) of the wave and the trough (bottom).

But when it comes to forecasting, it’s not just about a single wave. Most surf forecasts refer to significant wave height (Hs), which is defined as the average height of the highest one‑third of waves during a given time period.

So yeah—you could absolutely have a 1‑foot wave and a 4‑foot wave in a set, and the forecast might call it a 2‑foot day.

But hey, we’re surfers. We don’t make shit simple. We make it more complicated. Which is why we don’t use one but three different methods of measuring waves.

3️⃣ Three methods of measuring waves

We have the Bascom Method, developed by Willard Newell Bascom—one stands on the beach, aligns the horizon and wave crest, and measures from crest to average sea level. It’s considered more “fair” and rational in surf‑report‑world.

Then, of course, there’s the Hawaiian Scale, also called the “Traditional Scale.” Common in Hawaii and some pockets of surf culture. This method often measures from the back of the wave (rather than the full face) and tends to under‑call the size. For example: a wave with a 6.5 ft face might be called ~3 ft on the Hawaiian scale.

And finally: Face Height, or Surfable Wave Face Height. This one measures from the point a surfer would ride (from bottom of the face to the crest). One article explains that a 2 m wave (6.5 ft) by the Bascom method might be ~1.3 m (~4.2 ft) in surfable‑face measurement under that system.

If you’re using surf forecasting apps, some of them let you choose between “Face Height” or “Traditional” (Hawaiian) wave height units.

The body‑height approach we all use anyway

And this one you know already.

You can also measure waves in body‑height references:

1′ = ankle‑shin high; 2′ = knee‑thigh; 3′ = waist‑belly; 4′ = chest‑shoulder; 5′ = head high; 6′ = one foot overhead; 8′ = three feet overhead; 10′ = double overhead faces; 12′ = double overhead+; 15′ = triple overhead; 20′ = “very big.” Nice to know that an average surfer stands either 5 or 6 feet. LOL.

Wave math gets messier with reefs, period, and shape

Lest we forget that spot and reef geometry matter. A wave that looks “6 ft” at a beach break might be much bigger or smaller once you consider shallow reef, wave draw, or face steepness.

At the end of the day, having a number (say “8 ft”) doesn’t tell you period, steepness, wind, crowd, or reef—each of which affects risk and rideability. But you gotta feel for the big‑wave riders chasing world records when measuring whether they made it into the Guinness World Record still remains, somehow, subjective.