Now Reading: So you wanna be an aerialist?

-

01

So you wanna be an aerialist?

So you wanna be an aerialist?

Ever wanted to become an aerialist? I guess it would help to understand what it takes to start with.

Imagine a world in which no airs in surfing exist. It wasn’t that long ago, because an aerial only came onto the scene in the 1970s and came into its own in the 1990s, when it became its own branch of surfing with aerial specialists and aerial-only competitions.

From skate parks to surf breaks

Now, how did we get here? You may remember that surfing came before skateboarding, but skateboarding airs came first—and influenced surfing airs.

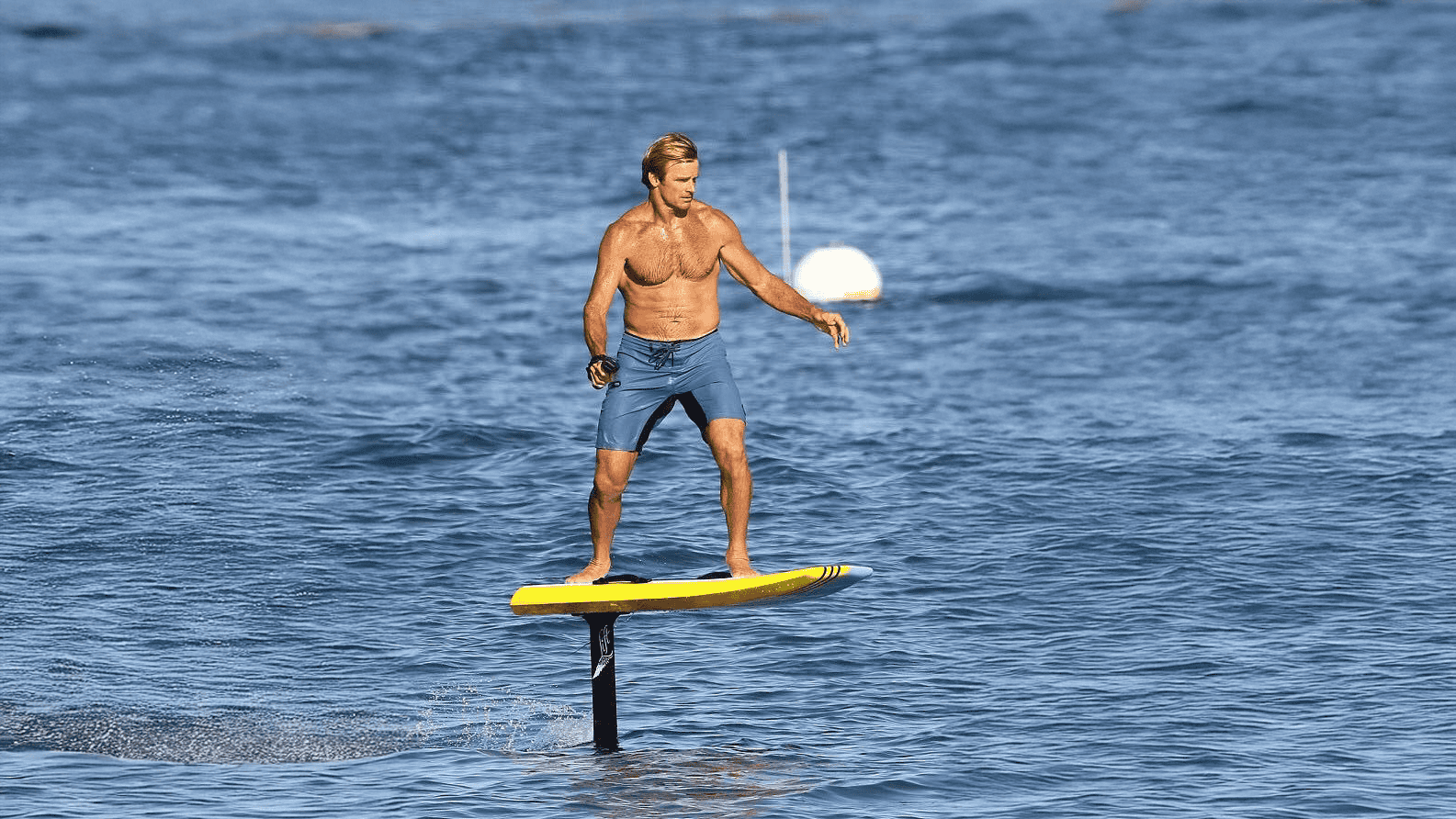

An aerial (or air) happens when a surfer launches herself off the wave crest into, well, air, performs one of the board-and-body-torquing maneuvers, and lands back on the wave face. Aerials tend to be performed in waves under six feet.

Matt Warshaw, the surfing historian, considers the aerial revolution a slow one. “Surfboards couldn’t be gripped and handled in the air as easily as skateboards, and waves, unlike pools, change shape constantly. The ‘chop-hop,’ an early and rightfully maligned aerial variant, was enough to keep most progressive surfers working on deep turns and tuberides,” he said.

The aerial revolution

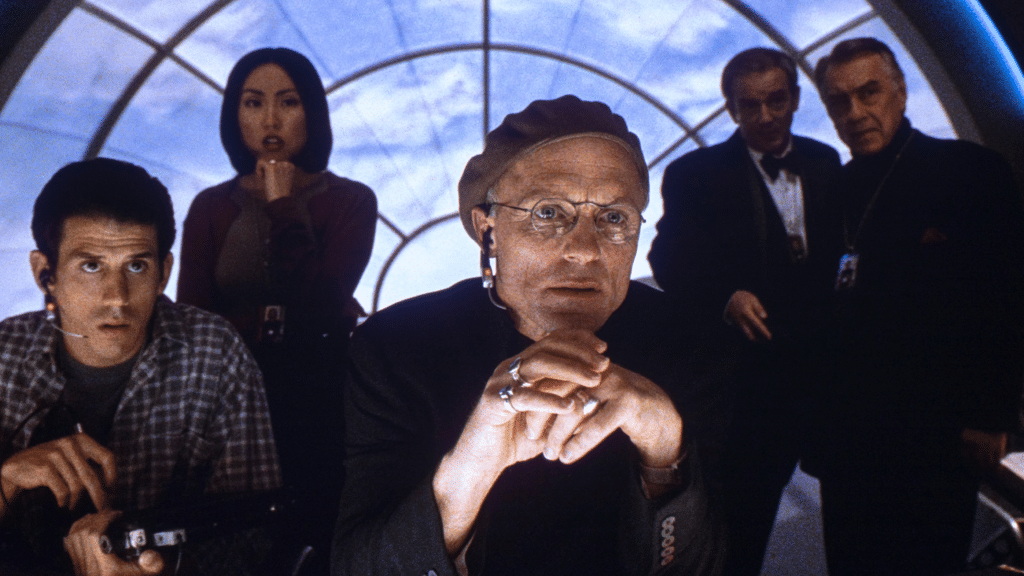

As slow as it might’ve been, the evolution of aerial surfing was pretty colorful. Early on, the surf media called the aerialists “flying squirrels,” and some surfers didn’t consider it true surfing.

But then, in the 1980s, John Holeman from the East Coast performed a 360-degree aerial rotation, and Christian Fletcher and Matt Archbold of San Clemente, CA, started lifting four or five feet above the crest—and everyone lost their shit about aerials.

The air vocabulary also grew, and we were rewarded with “mute air,” “indy air,” “slob air,” “madonna,” and “stalefish”—it’s all to do with hand placement on the board, you see. Then, Kelly Slater made aerials mainstream, and strapped tow-in pushed the evolution and air height even further.

Anatomy of an air

I found this description of what determines an air category in the EOS, and I’m bringing it to you verbatim:

“Aerials are categorized according to four factors:

- The rider’s position during lift-off; either frontside or backside.

- The positioning of the rider’s hands as he flies; either hands-free or with one or both hands gripping the edges of the board.

- The flight pattern of the board; usually a simple arc, a 180-degree spin, or a 360-degree spin.

- The board position on landing; either nose-forward or ‘reverse’ (tail first).

The surfer’s position relative to the board also comes into play; a ‘tweaked’ air, when the rider is at an angle to his board rather than centered over it, is more difficult. ‘Air’ is synonymous with ‘aerial’; ‘boost,’ ‘launch,’ ‘bust,’ and ‘punt’ have all been used as well.”

How to launch one yourself

What does it take to perform an air? I am definitely not speaking from experience, but it starts with wave selection. Look for a medium-sized, powerful wave with a strong lip to launch off. Then, you need to build speed by pumping. Stay in the pocket or curl of the wave!

As you approach the lip, perform a shallow bottom turn to maintain speed and angle your board to project upward—not straight up. Finally, coil your body like a spring before hitting the lip, then extend your legs and lift your arms to launch off the wave. A slight push with your front foot at the lip can help launch the board.

Once you get great at it, you can head to the Stab High competition sponsored by Monster Energy (you’ve just missed it—it was last week in Sydney).

Alas, Red Bull Airborne hasn’t taken place for a few years now. Shame, because I heard it gives you wiiiiings.